WDF is evidently putting all its Polish flock out to pasture, putting all its Polish cards on the table, and keeping its podcast silverware very well Polished (sorry about that). We’ve gone a bit Poland-obsessed in WDF towers, what with the announcement that we will be releasing a brand new podcast on Poland on 18th May 2018 called Poland Is Not Yet Lost recently being revealed. That announcement generated, I’m happy to say, a good bit of buzz, so with that trend in mind, I thought it’d be only right to introduce our stop off before we meet that new podcast head on.

A monument to Sobieski in Warsaw.

If you’re interested then, I’d like to present this article to you guys, where we look at 5 things you can expect from the upcoming 12 part biography on Jan Sobieski, releasing on this Friday 6th October. I should preface all this stuff by saying that this article is, one may argue, a bit cheeky. On the one hand of course it’s not and I can do anything I want because this is my blog, but on the other hand I have to mention that Jan Sobieski’s story is only available to Patrons at the $5 level and upwards. However, I should qualify this by saying that the first episode of the biography will be available to all you guys should you want a peek at what’s to come.

I hope that even if you have no intention of stopping by our Patreon and signing up at that level, you’ll still have a read here and be excited for what’s to come. Just to reiterate – Poland Is Not Yet Lost will be as free as WDF, so even if Sobieski isn’t your cup of tea, you’ll have a read here and get yourself psyched for what’s to come. There is, I must admit, a rather large amount for a history friend to be psyched about. So with that in mind then, here’s 5 things you can expect from the Jan Sobieski biography series.

By the way, if you want to have a listen to the first episode of the Jan Sobieski Bio before its release this Friday, go right ahead! --->>>>

#5: You’ll be provided with another perspective to experience this era through.

Sobieski in his coronation portrait, c. 1676.

The Long War is our current focus for the foreseeable future, as WDF counts down the days to the last siege of Vienna by setting the scene and examining the concerned parties. We’ve already begun to do this, and this story will take us to the end of 2017, when the climax of the siege in all of its glory will be revealed. I’ve already been immensely flattered with the feedback you guys have sent in, so I know this story is the right one for us right now, but what if you happened to be thinking to yourself at any point ‘well dang, I do love the narrative, but what did an apparent bystander in all of these developments think of what was going down?’

Well, that's where we come in with this Jan Sobieski series! The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth couldn’t be described as a bystander from the siege of course, since Polish winged hussars famously marched to victory outside its walls, but our coverage has certainly taken us deeper into the Habsburg-Ottoman rivalry than say, any alternative but very real rivalries at the time, such as that of the Commonwealth and the Ottomans. As we’ll see, the Ottomans were like the constant threat to the security and integrity of Poland, sending forth her terrible Tartars when the going was good, and launching a full-blown invasion when the going was bad. In Sobieski’s bio I hope to tell this story in more detail, but that’s not all we’ll get into.

Sobieski’s life and times stretched from the 1640s to 1690s, and during that timeframe, as past episodes of WDF will no doubt tell us, much was going on in Europe. The revolt of the Cossacks and their eventual siding with Russia, the Swedish deluges and the immensely important but seldom mentioned campaigns Poland launched against the Turks – all of these were critical cogs in a story we have yet to properly do justice to. Sobieski’s relevance in the 17th century is found in his presence through so many of the continent’s great events.

He travelled west to Europe at the closing stages of the Thirty Years War, and by the time of his death had taken part of in that other symbolic event of the century, the last siege of Vienna. Sobieski’s profile and prominence as much as his admirable skill and patriotism will be fully on display in this series, so if you want to have yourself another lens through which to view the events of the 17th century, Sobieski is your man!

#4: We’ll be telling the story of the man before the legend.

The battle of Chocim in 1673, a full decade before the events of Vienna, gave an indication of what Sobieski was capable of.

As we said, Sobieski lived and eventually ruled in a world which was wracked by warfare, but it’s only when we get into the meat and bones of this story that you’ll be able to appreciate the full extent to which this was the case. Not only was the Commonwealth involved in a set of wars from the 1640s onwards, but Sobieski played a not insignificant role in all of them, his presence and importance only growing with his age.

I am well aware that much legend surrounds Sobieski to this day, largely because what came after him wasn’t exactly what you’d call spectacular. However even before he showed up outside the walls of Vienna, and before he became King of Poland in 1673, Sobieski had a fair claim to at least being a commander of great importance and bravery at a time when his countrymen desperately needed him.

I will be taking my time in my examination of such a storied career, and I will make sure to place in context what Sobieski did right and what he did wrong. At the same time though, what will certainly come across to my listeners, especially those that, like me, knew little of Sobieski’s actual accomplishments before becoming King, was that Jan Sobieski was one of those figures that come about only every once in a while, which brings me to my next point.

#3: Jan Sobieski was an incredible guy…

Sobieski's victory at Vienna immortalised him, but before that event, the King of Poland was already well on his way towards cementing his legend.

It’s very hard to deny that Sobieski had that it factor which made men want to follow him and which netted him the woman of his dreams. A perfect moustache will only go so far in this regard – I think it’d be fair to say that Sobieski was a leader of men, and that his men respected him for the genuine concern he held for them and his country. This is demonstrated in his great military victories, when he managed to mobilise what men remained to take on and dismantle over and over again that lethal cocktail of Tartars and Cossacks which all to often ripped through the Polish heartland.

Sobieski was a noble with patriotic inclinations at a time when such inclinations were in the decline, a point I’ll get to, but it the consistent rescuing of the Commonwealth that Sobieski managed to pull off, often against apparently all odds and reasonable expectations, surely qualify him for a favourable historical reputation, right? Well actually, as we’ll come to discover, the narrative surrounding Sobieski today isn’t as rosy as you may expect, which brings us to point #2…

#2: …or was he?

A monument to Sobieski which was originally from Lvov, but which now resides in Gdansk (Danzig).

A side effect of covering a man like Sobieski is that you discover the different ways history has come to regard him. Norman Davies, the historian responsible for the iconic God’s Playground narrative on Poland’s history, heavily criticised Sobieski for committing the Commonwealth to a holy war alongside Russia, Austria and Venice at a time when what she truly needed was rest. In addition, we cannot ignore that Sobieski searched and grasped for a way to make his crown hereditary, against the express wishes of his noble peers who wished to maintain the crown’s elective status.

How do I respond to such critiques? The same way I do with most historical debates – by placing them in the context of the time. It is easy for us and Norman Davies to say that, after the last siege of Vienna, Sobieski should have sought peace with the Turks and rebuilt his kingdom. Yet, if he had done that, then Sobieski would have thrown away what seemed like a genuine opportunity for the Poles and their allies to avenge themselves upon the Ottomans for all the terrible woes that had been inflicted upon them over the last few decades, including the peeling off of large portions of historically Polish territory.

We cannot ignore these facts anymore than we can claim that Sobieski was some kind of perfect and totally benign ruler, but in this series I will do my best to be as fair as I can, while still giving Sobieski the credit he deserves.

#1: You’ll be given an introduction into this fascinating world – the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

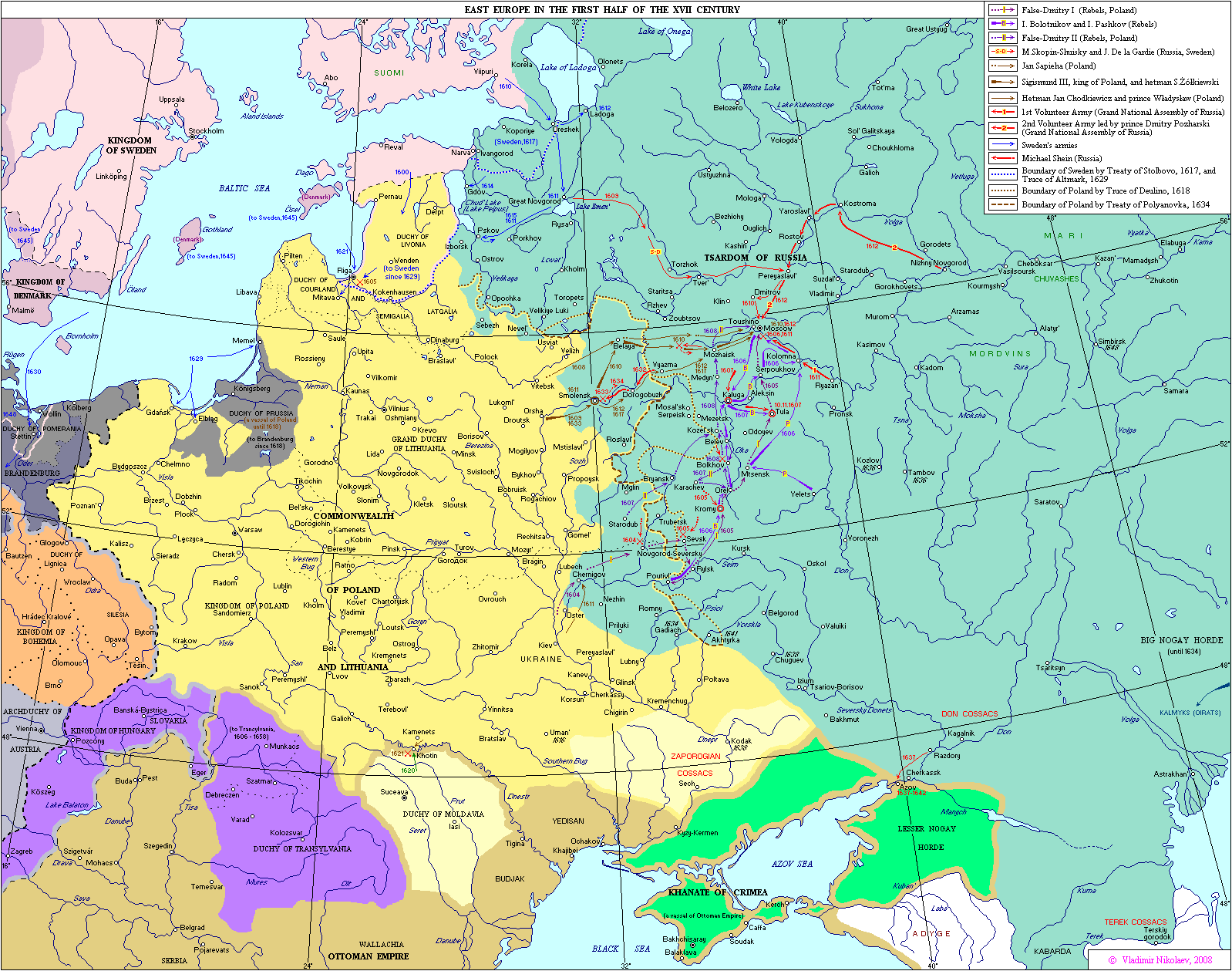

I think it’s fair enough to bill Sobieski’s biography as a prequel to Poland Is Not Yet Lost, not least because in the 12 episodes we capture the essence of what was to come in the Polish story. The Commonwealth occupied one of the largest stretches of territory on the continent, and boasted a population of about 10 million souls by 1700, yet her industry lagged behind, her administrations were inefficient and her resources scant, especially in comparison to her more centralised neighbours.

The Polish problem, as we’ll discover in more detail in our new podcast, was that the country was full of ideologues and theorists on how to best balance the contract between the nobility and the crown, at precisely the wrong time. On the borders of the Commonwealth, its neighbours nibbled away at its security, and the inability of the central government to properly mobilise or control its people or army led to a dilution of authority in some of the most vulnerable regions.

Poland-Lithuania started off the 17th century looking like this...

Halfway through the 1600s it looked like this...

And 100 years after Sobieski's death it looked like this. The task of the Sobieski bio is to set the scene for why this terrible transition of power occurred. The task of Poland Is Not Yet Lost is to tell that story.

Sobieski, as we’ll see, could already see this troubling process taking shape, and he was adamant that if the Commonwealth was to survive then it would need to be reformed with haste. Such reform could only come if the nobility and wealthier magnates of the Commonwealth put aside their petty jealousies and self-interests, and actively contributed towards the administration of Poland-Lithuania as had been done in the past. The liberum veto – such an infamous device of the Republic’s constitutional process in the 18th century – was merely a monster’s egg by the time of Sobieski’s death in 1696, but this monster would hatch and grow into an all-consuming nightmare so long as Sobieski’s peers and their offspring continued to see their estates as more important than their state.

As time went on, Sobieski's significant contribution to the last siege of Vienna became steeped in legend.

In a sense then Sobieski’s story is a tragic one for, surrounded as he was by both supporters and detractors, he began to experience even at the height of his fame a level of criticism which, at times, brought him to tears. Sobieski was not a thoroughly martial or ruthless dictator in any case. He may never even have sought the Crown had his wife not pushed him to stand for royal election, and throughout his reign he remained as true to his old character as he had always been. He was a fighter who preferred the fine arts, could never truly master French and deeply loved his wife. He was unquestionably a flawed character at a time when such men were a dime a dozen in Europe, yet he pushed through both his own limitations and those of the Commonwealth to produce something incredible – a flourishing, however fleeting, of a legend, of a name and of a people.

For this reason, it is fair to say that Sobieski put Poland-Lithuania on the map just in time for his successors to wipe it off. Those successors are still to come in our great and ambitious quest to tell the story of Poland, but I hope you guys will join me for its prequel, as we bring you the story of the man, the commander, the warrior, the lover and the King – Jan Sobieski.

********

Thanks for reading history friends! I hope you enjoyed a glimpse of what’s to come for WDF, and remember if you are in the mood, make sure to sign up on Patreon so that you can get your hands on Jan Sobieski’s story.